Marina Kaljurand speaks with Joseph Marks from Nextgov on norms and The Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace.

The Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace, launched in Munich last month, joins a complex tapestry of international bodies trying to impose rules of the road on the wild west of cyberspace.

What the Global Commission can add to the mix, Chairwoman Marina Kaljurand told Nextgovrecently, is a broad membership that spans former government officials, the private sector, legal experts, academics and technologists.

The commission also does not contain any current government officials, which will give commissioners more leeway to think boldly and creatively about what areas of cybersecurity norms and policies they want to tackle, said Kaljurand, a former foreign minister of Estonia and Estonian ambassador to the U.S., Russia and other nations.

» Get the best federal technology news and ideas delivered right to your inbox. Sign up here.

The most powerful international group focused solely on national cybersecurity, by contrast, the Group of Governmental Experts in Information and Communications Technology, is currently composed of 25 government representatives.

That means the GGE’s recommendations to the United Nations secretary general about norms nations should honor in cyberspace have great weight, but the group’s work is also often stymied by larger squabbles between the U.S., Russia, China and other nations.

The lack of a direct link to government will allow the Global Commission to move more nimbly, Kaljurand said. Commissioners’ goal, though, isn’t to promulgate cyber norms and policies for an ideal world but to develop norms that national governments will actually sign onto.

“I think we’ll have more flexibility than the GGE,” Kaljurand said. “But we have to talk to governments and we have to listen to governments because, in the end, we can [only] say we’ve completed our work if governments take on the policies and recommendations we suggest. We can’t be just a group of people not talking to governments or not listening to governments. In the end, we will give our products, our deliberations, our reports to governments.”

The commission, which is based in the Netherlands, was established by the Hague Centre for Strategic Studies and the East West Institute, both think tanks, and supported by numerous organizations, including the Internet Society and Microsoft.

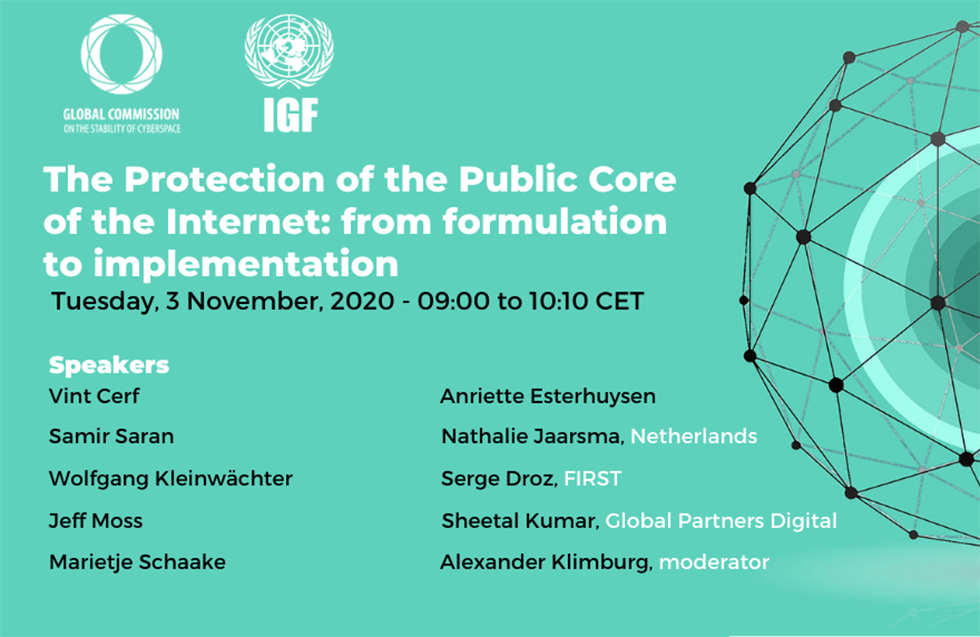

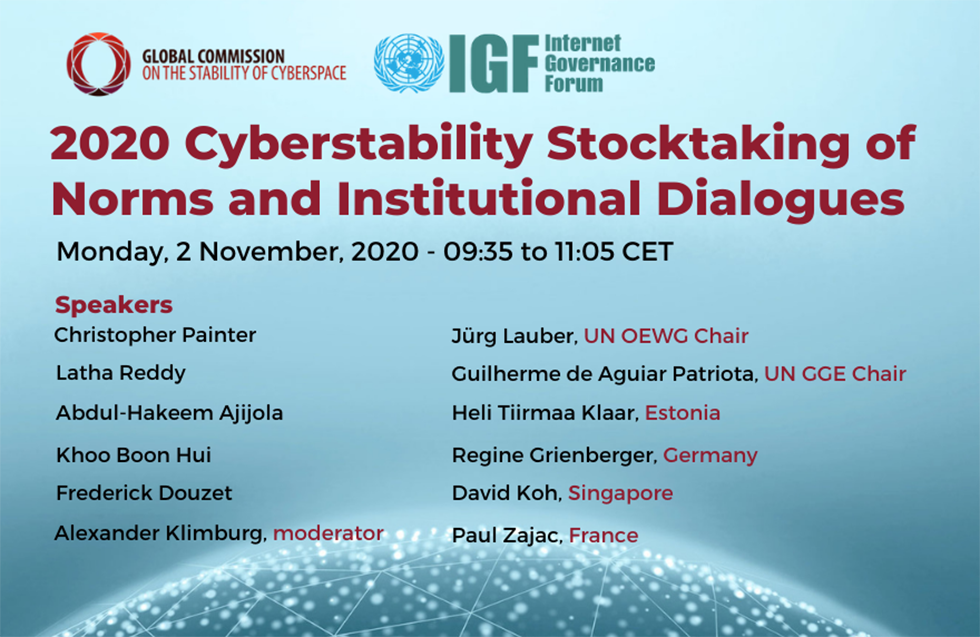

The commission is co-chaired by former Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff and former Indian government official Latha Reddy. Commissioners include DefCon conference founder Jeff Moss and Harvard academic Joseph Nye along with other representatives from India, Germany, Japan, Brazil, China, Russia and elsewhere.

Nextgov spoke with Kaljurand about the commission’s early work at the Estonian Embassy in Washington this week. The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity.

Nextgov: How have things been going so far? Have you settled on any topics to focus on?

Marina Kaljurand: We haven’t had full meetings yet. The launch was a month ago and we just had small group meetings. Those people who were in Munich sat together and we started discussing possible topics for research. I can’t say that we have agreed on a specific topic yet.

There are different fora already existing, so we see our role as complementary to those. Probably we will look into what GGE has been doing and continue to take on board some subjects from there, like not [cyber]attacking critical infrastructure, not attacking financial systems, supply chain safety. We’ll try to find something that is useful and important for both governments and the private sector.

Nextgov: You mentioned cyber norms from the GGE. There’ve also been cyber agreements at the G20 and there’s the Tallinn Manual, which discusses how to apply international law to cyberspace. Is there room for another international group in this area?

Kaljurand: I think that each and every discussion is very important and they all have their niche. The Tallinn manual is a deliberation of 20 international law experts. It’s their opinion. It has to be looked into by governments because only governments can apply international law.

The Tallinn manual has that mission. GGE is a forum for 25 government representatives. They have their mission. So, I think there is room for different bodies for discussions. It’s the result that’s important.

Nextgov: Will norms endorsed elsewhere, by the GGE or the G20 or the no commercial hacking agreement between the U.S. and China be a starting point?

Kaljurand: I think It will be up for discussion. There’s a lot happening already. We have to look at what’s been done already and map it. If there are some agreements bilaterally or regionally, yes, I think it would make sense to try to make them also global.

Nextgov: Some nations have criticized the GGE for not being inclusive enough. The commissioners announced so far don’t include much representation from the developing world. Does that concern you?

Kaljurand: We have two commissioners from Africa. We have a commissioner from Malaysia. So that region is represented.

I think the important thing is to find the balance in geography but also to include people who really care and who are committed and who will deliver. Because if we just look at geography, and don’t look at whether they’re doing interesting work in the field, it’s not going to work.

If we talk, for example, about the private sector, bring me someone who is as good as Microsoft on working with norms. They are just so efficient and they have taken the subject so seriously. They’re writing their own norms.

Nextgov: The GGE’s work has been hindered by broader disagreements between western nations and China and Russia and also by fundamental disagreements about how open the internet ought to be. Do you worry the commission will be hampered by the same things?

Kaljurand: We have to be very realistic about GGE. In GGE, we have the same ideological division that we have in real life. On one side, there are like-minded countries who see the benefits of the use of [information and communication technology]. On the other side, there are countries who see the use of ICT as a limitation to their sovereignty and to their authority and as having bad influence on their children. Read the strategy papers of Russia and China.

So, that’s the reality and we will not be able to solve in the GGE the questions that are not solved in real life. But at the same time, it’s the only forum like it is. I compare it to the United Nations. We’ve been reforming the United Nations now for I don’t know how many years. But it’s the best we have. It’s the same as the GGE. It’s the best we have. I think it’s very important that we have the GGE. I think that with each and every GGE we’re making some progress.

Nextgov: Can the Global Commission get more done?

Kaljurand: I think the global commission can agree on some norms and propose them to states—in critical infrastructure but also maybe some norms for the private sector. I think we’ll have more flexibility than the GGE.

For example, in 2013, Estonia’s proposed a new norm not to attack financial systems because we thought it’s so universal. Every country should be interested in agreeing to that because that’s the backbone of the economy. Yes, the same countries are on board, but years ago Russia was talking about not attacking financial systems. The Chinese are not against that. So, I think we can make progress on some questions.

Nextgov: President Donald Trump has generally opposed broad, global agreements of the sort you’re describing. Does that concern you?

Kaljurand: First of all, it’s very important that the U.S. stays engaged. It’s important for like-minded countries, it’s important for NATO, for the United Nations, for other organizations.

If I look at the recent appointments and recent statements here in Washington, I would say they’re encouraging.

Nextgov: You mean the appointment of White House Homeland Security Adviser Tom Bossert and White House Cyber Coordinator Rob Joyce?

Kaljurand: Yes, and what I hear the State Department is saying. At the moment, [it seems] there is an intention to continue with what the previous administration was doing in cybersecurity, especially in the field of norms and international law. That’s encouraging. But these are just first signals. We have to see who will be the people in the White House. Will [State Department Cyber Coordinator] Chris Painter stay? Who will be the undersecretary above him?

We have to look at all those appointments, but the first signs are encouraging. [Eds.: Bossert promoted international norms in cyberspace at a conference at the University of Texas at Austin, Thursday, calling them a key component in deterring adversary cyberattacks].

Nextgov: One early signal from the Trump administration is that Bossert criticized data localization [efforts by nations to limit their exposure to the global internet]. Might that be a topic?

Kaljurand: It’s too early to determine because we agreed that [at the commission’s first meeting] in June we won’t table anything. We’ll see what questions commissioners find important. After June, I can be more specific.

Nextgov: Might questions about the cybersecurity of election infrastructure and the influence operations such as the Russian operation during the U.S. election be topics for commission discussion?

Kaljurand: You can’t exclude election infrastructure because there are governments discussing whether election systems could be part of critical infrastructure. Critical infrastructure is not defined universally, which means every country decides what’s critical infrastructure for them.

As to information operations, we will talk about stability and security of cyberspace, but maybe not so much information operations.

Nextgov: Because that’s outside the scope?

Kaljurand: Yes, but it might influence the discussion and it might bring some topics to the table.

Nextgov: When do you expect the first reports to come out of the commission?

Kaljurand: We have a timeline of three years, but we want to be engaged through the whole process, so it’s not that we disappear for three years and then come back with the report. After our first second and third meeting, we’ll be happy to share what we discussed, what are research topics. Everything will be on our website.

Nextgov: Are you concerned that cyberspace simply develops too quickly for nations to adopt reasonable norms of behavior?

Kaljurand: I agree that everything in cyberspace is developing very rapidly. We don’t have an idea what will happen with internet of things and some other notions—quantum research, cloud computing. Still, [the commission] has more flexibility because the people are real experts in their fields. They don’t see just today’s developments. If there’s a platform that can look into the future, I’d say this one can do that.

As to norms, yes, developing norms takes time, explaining takes time, convincing governments takes time. So, we’ll try to be as quick and as flexible as possible, but the second part will be convincing governments to adhere to what we agree on.

Nextgov: Have we come as far as we should on cyber norms development to this point? Are you optimistic or cynical?

Kaljurand: I come from a small country where we trust and we very much respect international laws and norms. For us, it’s a guarantee of predictability, transparency and sovereignty. I think what GGE has done … is good. Has GGE done enough? GGE is not separate from real life. So, we can move as quickly as the countries are ready to.

I’m not naïve. I don’t think that if we have laws and we have norms the world is saved. We have criminal laws, we have national laws, we have international treaties that are violated. But it’s important for me that states say, even unilaterally, that they respect these norms, they’re going to follow these norms of responsible state behavior.

Cyber threats and cyber operations have been around for more than 20 years. Still, somehow states are not willing to agree to reach better international agreements. I very much hope we’re not waiting for cyber 9/11 to happen before we come seriously to the table and, instead of making political statements, start discussing, very pragmatically, what we, as states, can do to make cyberspace more safe and secure.