This article originally appeared in “Our Common Digital Future“, edited by Commissioner Dr. Samir Saran. This journal was published in the context of the Global Conference on Cyberspace 2017 (GCCS2017) in New Delhi, India.

In a prescient speech at the 2011 Munich Security Conference, the UK’s then-Foreign Secretary William Hague called for a collective response to the “dark side” of cyberspace. Hague wanted a “comprehensive, structured dialogue to begin to build consensus among like-minded countries to lay the basis for agreement on a set of standards on how countries should act in cyberspace.” Hague identified seven, principles to guide work on norms and pledged to host an international conference. The Global Conference on Cyberspace to be held in Delhi, is the fifth of the series of international conferences that Hague began.

With one exception – the 2015 Conference in Den Haag – these previous conferences have fallen far short of the original expectations. They strayed from Hague’s original idea of

bringing like-minded countries together to give norms “real political and diplomatic weight.” The conference organizers. The agendas tended to plow old ground, taking a “big

tent” approach that encompassed a range of issues related in some way to cyberspace. Political timidity guided these earlier Conferences.

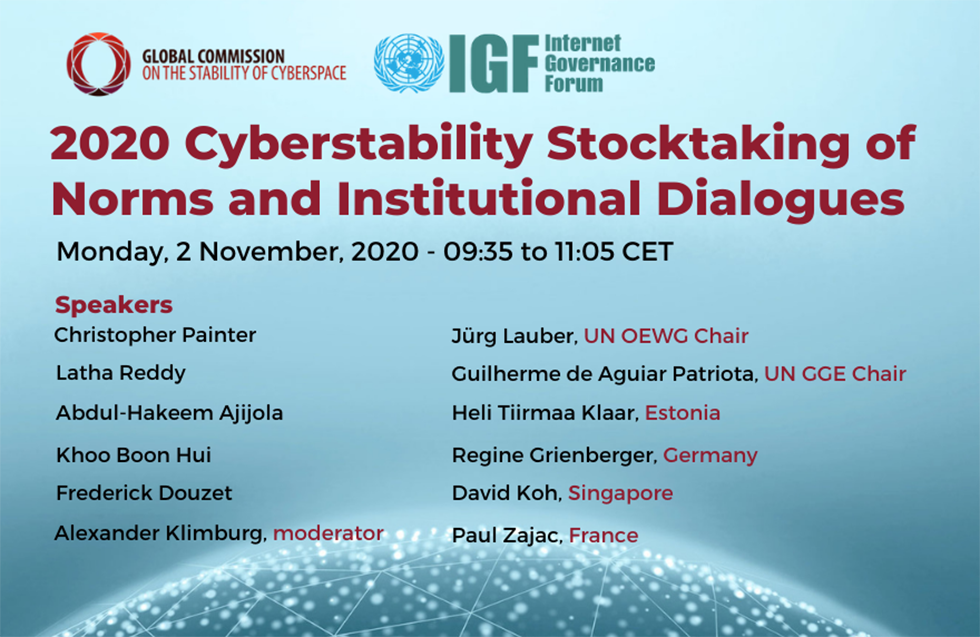

The Global Conferences took place against the backdrop of the work of the UN’s Group of Government Experts (GGE). Unlike most GGEs, where academic experts explore a topic, these “Cyber GGEs” were in fact proxy negotiations, with countries sending diplomats rather than academics. There have been five GGEs. The first in 2004 failed, largely because of American intransigence. The last, in 2017 also failed, this time because of deep disputes over international law. But the three GGEs in between 2004 and 2017 succeeded in reaching consensus on norms for responsible state behavior in cyberspace.

All three GGEs were difficult negotiations. The 2010 GGE Report laid out the international negotiating agenda: cooperation among states on norms, CBMS, and capacity building. The 2013 GGE Report reshaped the political landscape of cyberspace with its conclusions that internal law, sovereignty, and the UN Charter applied in cyberspace. This anchored discussion firmly in the context of existing international relations. Building on this, the 2015 Report laid out a sequence of norms to guide state behavior: its report was endorsed by the members of the UN General Assembly. The 2013 and 2015 GGEs provide recommendations on norms that can provide the basis for international cooperation on responsible state behavior.

Rumours of the GGE’s demise have been greatly exaggerated, but whether the failure to reach consensus in 2017 is only a pause in negotiation or whether the GGE process will be replaced by something else remains an open question. To be fair, the leading cyber powers – those who have the capabilities to exercise power in cyberspace – are not ready for agreement. Absent some truly pressing crisis, progress towards the goals Hague laid out will continue to be desultory.

One development that complicates defining the next step is that cybersecurity has gone from a specialized issue to one that touches many social and economic activities. All the GGE’s acted under the auspices the UN’s First Committee, which is responsible for disarmament and international security, but now a broad range of governmental and non-government bodies are attracted to the idea of developing norms. There is much room for many groups to work, as cybersecurity covers a broad range of issues, but the core issue of international security will remain closely held by states. Similarly, norms that do not win the acceptance of powerful states, such as the member of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council or the G-20, will not have useful effect. This is a hard truth from international politics, but this explains why the unfocused efforts of the Global Conferences before Den Haag made little progress.

The 2015 GCCS held in the Netherlands was an exception because it created formal structures on capacity building, information sharing, and a high-level Commission to consider how best to make cyberspace more stable and secure. These ongoing efforts are valuable, and the Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace (GCSC) most directly addresses the challenges of building stability in cyberspace.

The Commission has a challenge task and it faces some of the problems that afflict the GCCS series. The Commission’s twenty-seven members, drawn from industry, technical and civil society have varied expertise and nationalities. There are many different negotiating cultures in the group. Internet engineers want precise technical definitions; business people wants detailed contracts with subparagraphs for all contingencies. Diplomats know the valueof ambiguity in getting states to actually agree – details can be worked out once there is political agreement, not before. But all agree on the seminal idea behind the GCSC, that identifying norms for state and private sector behavior can increase stability and security.

There are many contending agendas in cyberspace and powerful voices to advocate them. The Commission is another voice and it faces significant but surmountable obstacles. The first is finding the balance between the role of the public and private sectors. The gravitational pull of the multistakeholder model that has guided internet governance is powerful and many advocate using it to define and implement cybersecurity norms. The second is deciding whether more norms are needed or the existing international law and treaties and the GGE Reports are enough. The temptation to propose additional norms is also powerful. The third is how to scope its work and whether to focus on international security or to bring in other issues.

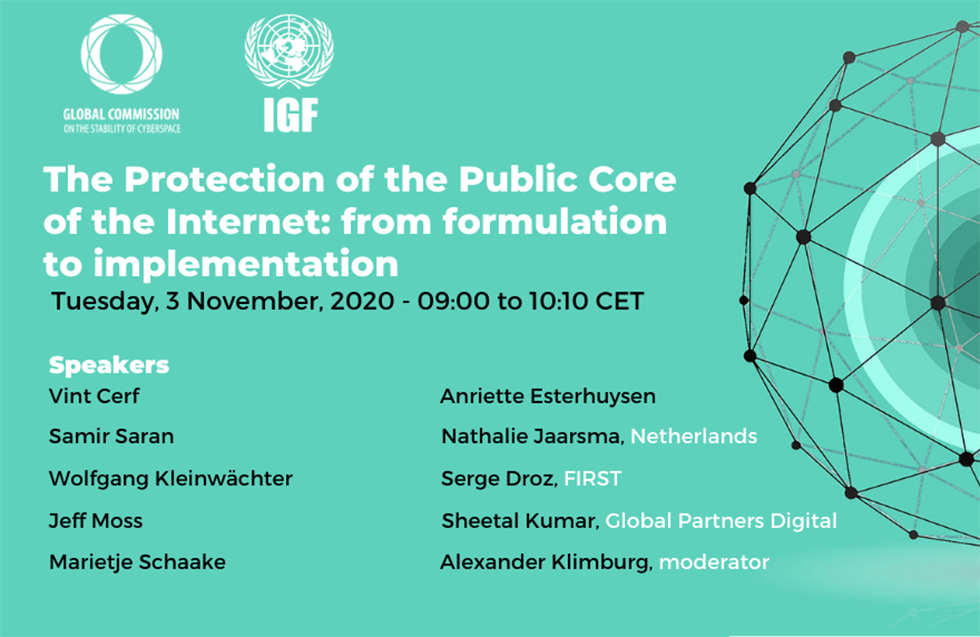

In the near term, the GCSC has considered proposing a norm to protect the public core of the internet, a proposal advanced at the 2017 GGE. The draft language being discussed is: States should not conduct or allow ICT activity within their territories that would affect the general availability of the core naming and forwarding functions of the internet.

While this language did not meet with universal agreement among GGE participant nations, the GCSC has the freedom to recommend it or an amended version of it for renewed consideration by international bodies like the G-20 or others.

In the long term, the GCSC could usefully consider how norms can be made more effective, the role of attribution in this, and whether a normative structure requires some kind of a formal, institutional framework or a convention. In considering all these issues the GSCS can help redefine the relationship of the multistakeholder model to international security.

The GCSC offers the best the opportunity to fulfil Hague’s wish for a comprehensive, structured dialogue to build consensus and lay the basis for agreement on norms. It can only make recommendations for others to act upon, but it has a unique status and with that, a unique opportunity to identify the path forward for stability in cyberspace.